Written by Jacqueline Courtenay, 25 May 2022

The following account covers the period of May 2020 - December 2020, and is written solely from the perspective of Jacqueline Courtenay.

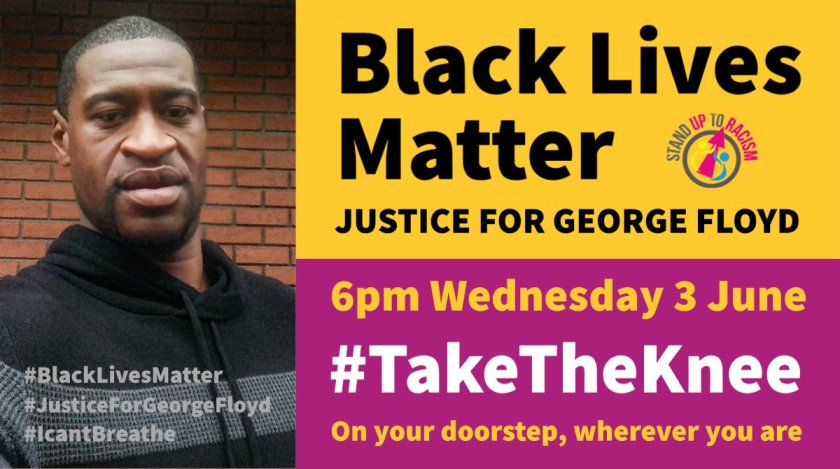

Today marks two years since the shockingly appalling killing of an unarmed black man named George Floyd by white police officer, Derek Chauvin on 25th May 2020. George Floyd. A name, we all now know well. His unlawful murder sent shockwaves across the world. In the days, weeks and even months that followed, protests took place in the name of anti-racism, people took to the streets and demanded change with their feet. Some of us marched. Some of us rallied. Some of us bent a knee. Our media coverage was awash with hand-written banners stating epithets such as “Black Lives Matter” and “silence = violence”. From Minnesota to Myanmar, the death of George Floyd in the summer of 2020 created a ripple effect of one international rally against racist police brutality after another. The killing of George Floyd forced everyone to talk about race.

On this second anniversary, I would like to share my account of what went on at my workplace (which will be referred to as “my Workplace” from here on) in the days following the killing of George Floyd and how, I, as the then co-chair of the internal Black affinity network (which will be referred to as “the Network” from here on) contributed to the various initiatives that arose in the aftermath.

Listening Sessions

Within a few days of George Floyd’s killing, the Network quickly sprang into action. We organised a listening session to provide support to fellow Black colleagues as we all processed the situation unfolding in America. The session, attended by over 100 colleagues, became the first of many moving listening sessions held throughout the summer of 2020 at my Workplace.

In the weeks that followed, I was invited to open several listening sessions. I supported the Head of a department with an entity-wide employee listening session, which saw Black colleagues as well as allies use the space to reflect, share and listen. I was also invited by several business area heads to share my experiences with their teams.

Throughout the course of these listening sessions, the pandemic was raging on and I was in the early stages of a pregnancy. Now, as anyone who works in midwifery knows, high emotion is the last thing a pregnant woman needs. Nonetheless, like many black people who work in predominantly white spaces, I became hyper-visible at this time and on several occasions, as a network lead, I was thrust into the spotlight to deliver incredibly emotional accounts of my experiences as a black person and black professional. Could I have declined? Yes, absolutely but I said yes to these invitations because deep down I felt that the summer of 2020 was a one time only event – in that, in terms of the workplace, there would probably never again be a chance to talk about race in the same open and honest way. Two years on, the appetite for talking about race has dwindled, so I think I was right to say yes. I am glad I overcame the nervousness of facing predominantly white colleagues and divulging to them my inner most thoughts on and experiences of racism. As much as I agree with Reni Eddo-Lodge’s book, in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, it was indeed time to talk to white people about race.

The most visible of these listening sessions was when I was asked to address the global HR team about my experiences of race and racism in the workplace. I have included the transcript of this speech at the end of this post.

Influencing the Race Action Plan

Going back to the week after George Floyd was murdered, the office of my Workplace’s CEO contacted me and my then fellow Network co-chair inviting us to meet with him. The aim was to discuss what Black colleagues needed at that time and when we met on June 8th, 2020, we used the opportunity to stress the importance of not only issuing a statement acknowledging the killing and the impact it may have had on Black colleagues, but also the importance of seriously tackling race at work.

On June 10th, 2020, taking on board many of the points we raised, the CEO published a powerful statement including a 6-point action plan for tackling racial inequality in the workplace. This meeting became the first of several open, honest, and frank discussions between the Network leadership team and my Workplace’s most senior leadership about race and race equality.

On this second anniversary of George Floyd’s murder, I’d like to direct my focus on key decision makers, senior leaders, and middle management at my Workplace and indeed at all other organisations who pledged to do more and to do better back in 2020.

I hope we will all renew our efforts in acting against racism and bias in our workplaces and will once again, place a serious focus on action. To conclude my reflection on the monumental summer of 2020, please see below the transcript of my speech to my Workplace’s global HR team.

Listening Session, Thursday 2 July 2020

Transcript of Jacqueline Courtenay’s address to the global HR team via Zoom

Hello, so I have just a few minutes to share my experience as a black person. Please note what I share might feel shocking or come across quite strong, but it is only meant to provoke thought and stimulate discussions as we all try navigating and working through things at this time.

So, telling you what it’s like, for me, that means:

– Telling you that whilst I wear a smile professionally, I live in fear even though to many people, the black experience isn’t that bad, it’s not like we’re slaves anymore is it? And whilst I’d love to agree wholeheartedly, the true things are still quite terrible for people like me.

– It means sharing another fear of mine. How I worry endlessly about my younger brother who at 19 and with about 10 years between us, he towers over me and due to his tallness to some with prejudices he may seem imposing as a young black man. How I fear for him whenever he goes out simply because there is a high chance, he might run into a prejudiced person who sees a threat in his colour before seeing the humanity or worse still a police officer who assumes he looks like every other IC3 male. I fear this because there’s a massive chance that the quiet, caring, non-swearing, non-alcohol drinking, comic-book loving, skilled artist and prospective architectural student, who spoke at my wedding and brought tears to everyone’s eyes with his moving wise words won’t be seen as anything but black and male and therefore a threat.

– It means telling you about my mum who routinely faced what we now call microaggressions in the early 90s, when she worked in healthcare and the specific time, she was ushered into a backroom along with all the other black members of staff and kept in there whilst a news team came to their ward and spoke with the white members of staff.

– It means telling you the white colleague who was pleased I had changed my surname after getting married because my Ghanaian maiden name was too long for her to keep typing out in emails.

– It means telling you about the time when how not one but two, smiling white women after observing my daughter for a while, approached me and stressed how lucky I am for having a mixed race daughter with loose curly hair, resembling the European hair of her father more of mine African – then I could share how my stomach tightened as they pointed to their own – half white, half black, mixed race kids with a look of disappointment, indicating they hadn’t been as fortune. Did they realise how offensive that was to me, given the connection I shared with their kids?

– It means delving into my early childhood, a time in primary school, during lunchtime when a 6-year-old me was told by my white classmate [name redacted], why I don’t go back to where I came from. Realising that early on that I couldn’t make off-the cuff remarks about the cold weather, because I was different. She told me that I should be happy to be here or leave if I was going to complain. Sounds like a prequel to Brexit if you ask me.

– It means I could tell you about a speech I wrote in year 9, entitled ‘what is in a word’ detailing how I felt about the word ‘black’ a word which as an adjective it represents tragedy, disaster, calamity, ruin, darkness, and dirtiness, I could tell you how gutting it felt to me at 14 to realise that in comparison, whiteness signifies, purity, lightness, and innocence. I could tell you how to this day I grimace, knowing how Africans came to be called Black, how Europeans who coined the term, used it as a tool for division and rule.

I’ve shared all these things, to appeal to you as human beings, to help you understand how it feels to be black. I’d like you to ask yourselves; in light, of all that has happened since the killing of George Floyd, what have you learned about the experience of blackness and the negative treatment of black people in our world? Considering our CEOs fantastic statement, do you personally intend to do differently to change things in our workplace?

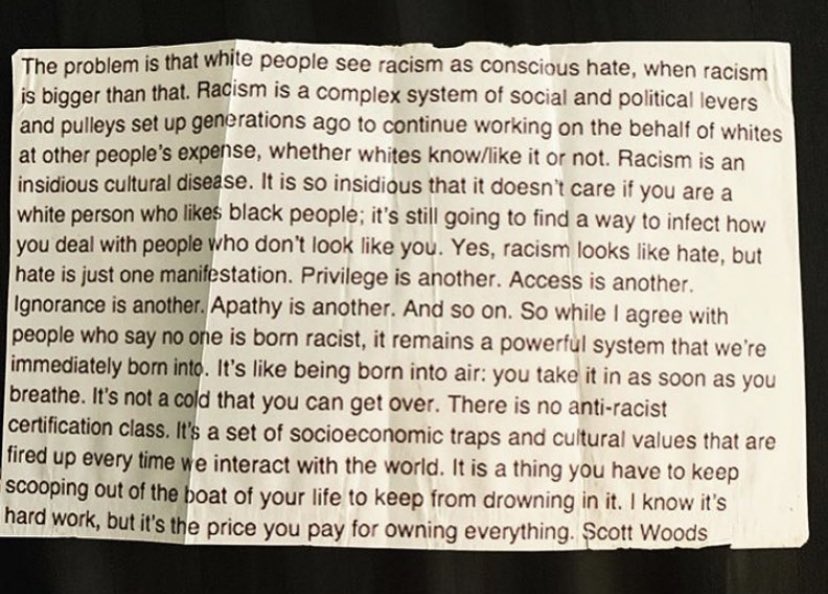

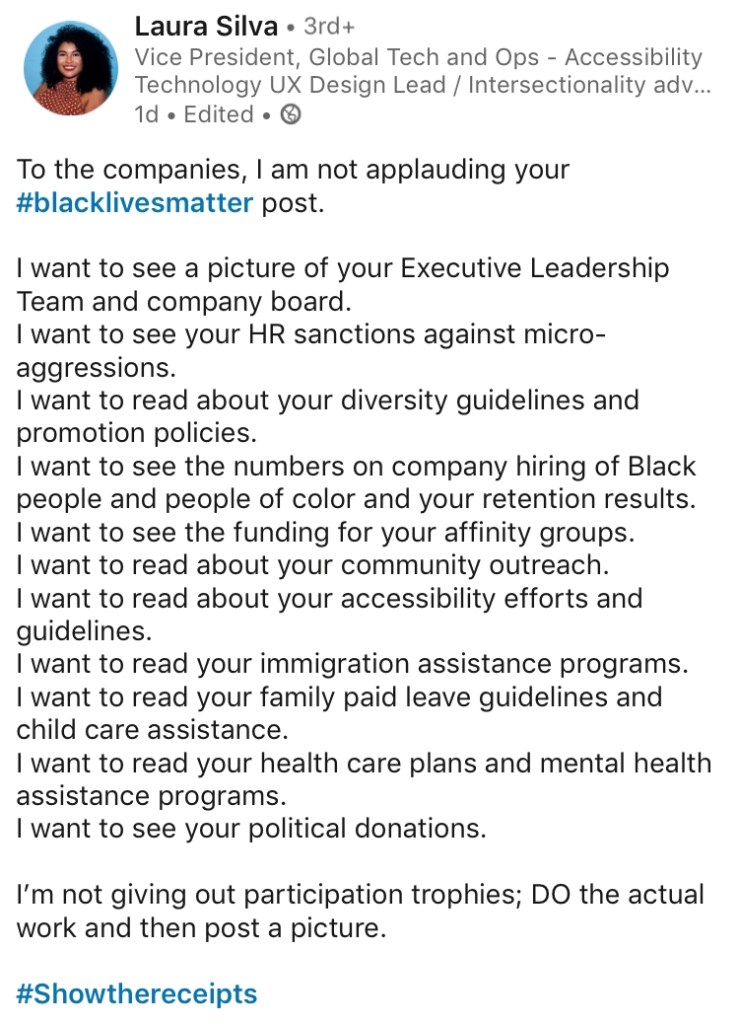

I ask this because we’ve all been watching as the Black Lives Matter movement has moved into the mainstream, which as a result we’ve seen some symbolic changes. Whilst symbols matter, people aren’t marching streets to change the cover of Uncle Ben’s rice packaging, what we’re really asking for is deep institutional change and letting go of the biases we inherit. And so, another question for you is, considering the statement from our CEO, do you think we will see change in this institution?

We are all privileged to work under the leadership of our CEO, a financial markets heavyweight, who isn’t afraid to tackle racism and I’m proud he even calls it that than using some other convoluted term. He’s bold. But not just that, as an organisation we’ve done great work. We have established a Black Employee Network. We’ve got policies to tackle discrimination. We’ve got a whistleblowing policy to make it easier for people to come forward. We’ve reviewed hiring practices to reduce bias. We’ve got unconscious bias training, there’s still something else. There’s still something missing. In some places, anonymous CVs are used to curb name-based racism. Perhaps we should do that. But what we also haven’t done is have sticky, uncomfortable conversations about how the external environment impacts what goes on here and pushes against our internal efforts to bring about change. Hopefully conversations like this, which I commend (name redacted) for initiating, will help move the conversation forward.

Perhaps we need to openly discuss how it is that the city got its wealth. Perhaps we still need to understand why racism still lives in the hearts and minds of so many. Perhaps we still need to talk openly about the fact that the British taxpayer only finished paying government debt in 2015, that was established over 200 years ago to compensate British slave owners who had lost earnings after slavery was abolished. Perhaps we need to speak openly about the private-school-to-private sector pipeline that distorts the true reflection of London in City firms. Perhaps we need to investigate why it is that across the City firms HR teams’ band the words “diversity”, “inclusion” and “unconscious bias” around but all too often these same teams do not embody or represent the diversity in their own teams. Perhaps we should talk about how deeply ingrained all of this is when we see how the Home Office treats black people, that the Windrush scandal wouldn’t have happened to the French-British community but happened very easily, very quietly and very routinely to British-Caribbean’s and British-Africans. Until we’ve confronted these truths and renounced the reprehensible actions of the past and present, ask yourself, will anything change?

Not to seem pessimistic but my hopes aren’t that high in truth, and why is that? Well because, race is configured very strategically in the UK. British racial affairs until recently, all took place abroad. Instead of going to watch the latest lynching’s as people did in early 20th century America, comparatively British people were oblivious to the screams of slaves being lashed or dipped into boiling liquor until their skin peeled off or had boiling water poured down their throats by British slave owners, like Arthur William Hodge, because none of this happened on British soil. It happened in the West Indies. And instead of hearing about this violence in the British Caribbean or the brutal colonialism that rampaged through Ghana where my family come from, British people of the early 20th century instead heard about the salvation British missionaries brought through God’s word, to the ‘savage’ West coast of Africa. Our civil rights movements even happened abroad, run by men like Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana fighting for independence from the British. It makes sense then why to many people, the matter of race has nothing to do with Britain. But Afua Hirsch told us when she spoke in our theatre last year (i.e., 2019) about the mills, still standing in picturesque English towns and their direct links to British slavery. We haven’t spoken about any of this not as a society and not as an organisation, it is still the elephant in the room. But it matters, race has everything to do with the UK and as British brand with a rich history, race needs to matter to our Workplace.

We don’t all come to this with the same knowledge or understanding, but at a very foundational level, when it comes to the diversity we have in the city of London: we are here, because you were there. Black people in the UK are descendants of colonialism. But if you didn’t know that you were there, you will find what I’m saying confusing. I mean I was born here, went to school here, went through the same curriculum which failed to teach any of us the details of how Britain became Great. But being black means that because racism and hostility greet you in day-to-day life, you find yourself pouring into the historical texts, exploring the histories to centre you, to bring some meaning to all the injustices you face. If you aren’t black, I get why doing that may not seem so pressing to you. It’s just like having an injury, unless you’ve experienced that same injury, you may never understand the depths of that pain though you may sympathise.

The failure to educate us about race at school, has done us all a huge disservice. But learning isn’t just for the young, life is a teacher as my mum says, and learning is lifelong. So, it is vital that you join the conversation. It is vital that we learn the true stories of British empire and imperial rule, it is vital that we come to terms with it, that we aren’t too quick to defend the 500-year system by jumping to say, “but we abolished slavery!”

Whilst I am happy about the statement from our CEO recently and hopeful, on a societal level I am mostly weary and sceptical about how genuine this moment of change is, because none of what I’ve said is new, none of what we’ve seen in the George Floyd case is new, the history is not new, it’s there. What is new is, to quote the writer Gary Younge, “this time it’s multiracial, it’s young, and it’s global”. It’s playing out in different places and so it feels like change is in motion. It’s just up to individuals in positions of power, like yourselves in HR, to choose to pick up the baton because this is a marathon. But if you think we have done enough, if you think all this chat about race is redundant, tired and unnecessary, if you think the work is done, if you think there are no wrongs to right, then in the words of white American educator, Jane Elliot, my last question for you is: please raise your hand or unmute yourself and say ‘yes’ if you think things are in such good a position that you would like Black people in our workplace, in our industry and in our world are treated?

End

Thanks for reading.

Leave a comment